Margaret Thatcher

The "Scots" that wis uised in this airticle wis written bi a body that haesna a guid grip on the leid. Please mak this airticle mair better gin ye can. |

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, LG, OM, PC, FRS, FRIC (née Roberts; 13 October 1925 – 8 Apryle 2013) wis a Breetish stateswumman, wha sert as Prime Meenister o the Unitit Kinrick frae 1979 tae 1990 an as Leader o the Conservative Pairty frae 1975 tae 1990. She wis the langest-serrin Breetish prime meenister o the 20t yearhunner, an the first wumman tae haud the office. A Soviet jurnalist cried her The Airn Leddy, an eik-name that becam associatit wi her uncompromisin politics an leadership style. As Prime Meenister, she implementit policies that hae come tae be kent as Thatcherism.

Baroness Thatcher | |

|---|---|

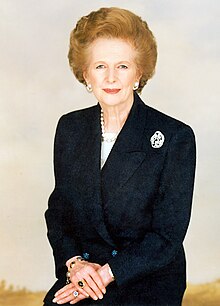

Thatcher c. 1995–96 | |

| Prime Meenister o the Unitit Kinrick | |

| In office 4 Mey 1979 – 28 November 1990 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Depute | Geoffrey Howe (1989-90) |

| Precedit bi | James Callaghan |

| Succeedit bi | John Major |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 October 1925 Grantham, Lincolnshire, Ingland |

| Dee'd | 8 Apryle 2013 (aged 87) Lunnon, Ingland |

| Naitionality | Breetish |

| Poleetical pairty | Conservative |

| Spoose(s) | Sir Denis Thatcher, Bt. (m. 1951-2003, his daith) |

| Relations | Alfred Roberts (faither) |

| Bairns | Mark Thatcher, Carol Thatcher |

A resairch chemist afore acomin a barrister, Thatcher wis electit Memmer o Pairlament for Finchley in 1959. Edward Heath appyntit her Secretar o State for Eddication an Science in his 1970 govrenment. In 1975, Thatcher defeatit Heath in the Conservative Pairty leadership election tae acome Leader o the Opposeetion an acame the first wumman tae lead a major poleetical pairty in the Unitit Kinrick. She acame Prime Meenister efter winnin the 1979 general election.

On muivin intae 10 Downing Street, Thatcher introduced mony poleetical an economic initiatives intendit tae reverse heich unemployment an Breetain's struissles in the wauk o the Winter o Discontent an an ongangin recession.[nb 1] Her poleetical filosofie an economic policies emphasised deregulation (parteecularly o the financial sector), flexible labour mercats, the privatisation o state-awned companies, an reducin the pouer an influence o tred unions. Thatcher's popularity in her first years in office waned amid recession an heich unemployment, till veectory in the 1982 Falklands War an the recoverin economy brocht a resurgence o support, resultin in her decisive re-election in 1983. She narraely escapit an assassination attempt in 1984.

Thatcher wis re-electit for a third term in 1987. In this period her support for a Community Charge (referred tae as the "poll tax") wis widely unpopular, an her views on the European Commonty war nae shared bi ithers in her Caibinet. She resigned as Prime Meenister an pairty leader in November 1990, efter Michael Heseltine lencht a challenge tae her leadership. Efter reteerin frae the Commons in 1992, she wis gien a life peerage as Baroness Thatcher (o Kesteven in the Coonty o Lincolnshire) whilk enteetlt her tae sit in the Hoose o Lairds. Efter a nummer o wee straiks in 2002, she wis advised tae reteer frae public speakin. Nanetheless, she managed tae pre-record a eulogy tae Ronald Reagan afore his daith, whilk wis braidcast at his funeral in 2004. In 2013, she dee'd o anither straik in Lunnon, at the age o 87. Ayeweys a controversial feegur, she haes been laudit as ane o the greatest an maist influential politeecians in Breetish historie, even as arguments ower Thatcherism perseest.

Early life an eddication

eeditThatcher wis born Margaret Hilda Roberts on 13 October 1925, in Grantham, Lincolnshire. Her faither wis Alfred Roberts, oreeginally frae Northamptonshire, an her mither wis Beatrice Ethel (née Stephenson) frae Lincolnshire.[2] She spent her bairnheid in Grantham, whaur her faither awned twa grocery shaps.

Margaret Roberts attendit Huntingtower Road Primary School an wan a bursary tae Kesteven and Grantham Girls' School.[3] Her schuil reports shawed haurd wark an continual impruivement; her extracurricular activities includit the piano, field hockey, poetry recitals, soummin an walkin.[4][5] In her upper saxt year she applee'd for a bursary tae study chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford, a weemen's college at the time, but she wis ineetially rejectit an wis offered a place anerly efter anither candidate widrew.[6][7] Roberts arrived at Oxford in 1943 an graduatit in 1947 wi Seicont-Cless Honours in the fower-year Chemistry Bachelor o Science degree, specialisin in X-ray crystallography unner the superveesion o Dorothy Hodgkin.[8][9]

Roberts jyned the local Conservative Association an attendit the pairty conference at Llandudno in 1948, as a representative o the University Graduate Conservative Association.[10] Meanwhile she acame a heich-rankin member o the Vermin Club,[11][12] a group o gressruits Conservatives formed in response tae a derogatory remerk aboot the pairty.

Ane o her Oxford friends wis an aa a friend o the Chair o the Dartford Conservative Association in Kent, wha war leukin for candidates.[10] Offeecials o the association war sae impressed bi her that thay askit her tae applee, even tho she wis nae on the Conservative Pairty's approved leet: she wis selectit in Januar 1951, aged 25, an addit tae the appruived leet post ante.[13] At a dinner follaein her formal adoption as Conservative candidate for Dartford in Februar 1951 she met Denis Thatcher, a successfu an walthy divorced businessman, wha drave her tae her Essex train.[10][13] In preparation for the election Roberts muived tae Dartford, whaur she supportit hersel bi wirkin as a resairch chemist for J. Lyons and Co. in Hammersmith, pairt o a team developin emulsifiers for ice cream.[10][14] Shortly efter her mairiage, she an her husband begoud attendin Anglican services an wad later convert tae Anglicanism.[15][16]

Early political career

eeditIn the 1950 an 1951 general elections, Roberts wis the Conservative candidate for the safe Labour seat o Dartford. The local pairty selectit her as its candidate acause, tho nae a dynamic public speaker, Roberts wis well-prepared an fearless in her answers. She attractit media attention as the youngest an the anerly female candidate.[17][18] She lost on baith occasions tae Norman Dodds, but reduced the Labour majority bi 6,000, an then a further 1,000.[17] During the campaigns, she wis supportit bi her parents an bi Denis Thatcher, wha she mairied in December 1951.[17][19]

Member o Pairlament: 1959–1970

eeditIn 1954, Thatcher wis defeatit whan she socht selection tae be the Conservative pairty candidate for the Orpington bi-election o Januar 1955. She chuise nae tae staund as a candidate in the 1955 general election, in later years statin: "I really just felt the twins were ... only two, I really felt that it was too soon. I couldn't do that."[20] Efterwart, Thatcher begoud leukin for a Conservative sauf seat an wis selectit as the candidate for Finchley in Apryle 1958 (narraely beatin Ian Montagu Fraser). She wis electit as MP for the seat efter a haurd campaign in the 1959 election.[21][22] Benefitin frae her fortuinate result in a lottery for backbenchers tae propone new legislation,[23] Thatcher's maiden speech wis in support o her private member's bill (Public Bodies (Admission to Meetings) Act 1960), requirin local authorities tae hauld thair cooncil meetins in public.[24]

Thatcher's talent an drive caused her tae be mentioned as a futur Prime Meenister in her early 20s[23] awtho she hersel wis mair pessimistic, statin as late as 1970: "There will not be a woman prime minister in my lifetime – the male population is too prejudiced."[25] In October 1961 she wis promotit tae the frontbench as Pairlamentar Unnersecretar at the Meenistry o Pensions an Naitional Insurance bi Harold Macmillan.[26] Thatcher wis the youngest wumman in history tae receive sic a post, an amang the first MPs electit in 1959 tae be promotit.[27]

Bi 1966, pairty leaders viewed Thatcher as a potential Shaidae Cabinet member. James Prior suggestit her as a member efter the Conservatives' 1966 defeat, but pairty leader Edward Heath an Chief Whip Willie Whitelaw insteid chuise tae promote Mervyn Pike as the Shaidae Cabinet's anerly wumman member.[27] At the Conservative Pairty conference o 1966 she criticised the heich-tax policies o the Labour govrenment as bein steps "not only towards Socialism, but towards Communism", arguin that lawer taxes served as an incentive tae haurd wark.[28] Thatcher wis ane o the few Conservative MPs tae support Leo Abse's Bill tae decriminalise male homosexuality.[29] She an aa votit in favour o David Steel's bill tae legalise abortion,[30][31]

Efter Pike's reteerment, Heath appyntit Thatcher tae the Shaidae Cabinet[27] as Fuel an Pouer spokesman.[32] Shortly afore the 1970 election, she wis promotit tae Shadow Transport spokesman an later tae Eddication.[33]

Eddication Secretar: 1970–1974

eeditThe Conservative Pairty unner Edward Heath wan the 1970 general election, an Thatcher wis subsequently appyntit tae the Cabinet as Secretar o State for Eddication an Science. In her first months in office she attractit public attention as a result o the govrenment's attempts ae cut spendin. She gae priority tae academic needs in schuils.[34] She imponed public expenditur cuts on the state eddication seestem, resultin in the aboleetion o free milk for schuilchilder aged seiven tae eleiven.[35] She held that few childer wad thole if schuils war chairged for milk, but agreed tae provide younger childer wi a third o a pint daily, for nutreetional purposes.[35] Cabinet papers later revealed that she opponed the policy but haed been forced intae it bi the Thesaury.[36] Her deceesion provoked a storm o protest frae Labour an the press,[37] leadin tae the moniker "Margaret Thatcher, Milk Snatcher".[35][38] She reportitly conseedered leavin politics in the eftermath an later wrate in her autobiografie: "I learned a valuable lesson [from the experience]. I had incurred the maximum of political odium for the minimum of political benefit."[37][39]

Leader o the Opposeetion: 1975–1979

eeditThe Heath govrenment continued tae experience difficulties wi ile embargoes an union demands for wage increases in 1973 an lost the Februar 1974 general election.[37] Labour formed a minority govrenment an went on tae win a narrae majority in the October 1974 general election. Heath's leadership o the Conservative Pairty leukit increasinly in dout. Thatcher wis nae ineetially the obvious replacement, but she eventually acame the main challenger, promisin a fresh stairt.[40] Her main support came frae the Conservative 1922 Committee,[40] but Thatcher's time in office gae her the reputation o a pragmatist instead o an ideologue.[23] She defeatit Heath on the first ballot an he resigned the leadership.[41] In the seicont ballot she defeatit Whitelaw, Heath's preferred successor. The vote polarised alang richt–left lines, wi the region, experience an eddication o the MP an aa haein thair effects. Thatcher's support wis stranger amang MPs on the richt, thae frae soothren Ingland, an thae wha haed nae attendit public schuils or Oxbridge.[42]

Thatcher acame Conservative Pairty leader an Leader o the Opposeetion on 11 Februar 1975;[43] she appyntit Whitelaw as her depute. Heath wis niver reconciled tae Thatcher's leadership.[44] In addeetion tae opposeetion tae Keynesian ecenomics, Thatcher wantit tae prevent the creaution o a Scots assembly. She tauld Conservative MPs tae vote against the Scotland and Wales Bill in December 1976, which wis defeatit, an then whan new Bills war proponed she supportit amendin the legislation tae allae the Inglis tae vote in the 1979 referendum on devolution.[45]

Breetain's economy during the 1970s wis sae waik that Foreign Meenister James Callaghan wairned his fellae Labour Cabinet members in 1974 o the possibility o "a breakdown of democracy", tellin them: "If I were a young man, I would emigrate."[46] In mid-1978, the economy begoud tae impruive an opeenion polls shawed Labour in the lead, wi a general election bein expectit later that year an a Labour win a sairious possibility. Nou Prime Meenister, Callaghan surpreesed mony bi annooncin on 7 September that thare wad be na general election that year an he wad wait till 1979 afore gangin tae the polls. Thatcher reactit tae this bi buistin the Labour govrenment "chickens", an Leeberal Pairty leader David Steel jyned in, criticisin Labour for "running scared".[47] The Conservatives attacked the Labour govrenment's unemployment record, uisin advertisin wi the slogan "Labour Isn't Working". A general election wis cried efter Callaghan's govrenment lost a motion o na confidence in early 1979. The Conservatives wan a 44-seat majority in the Hoose o Commons an Thatcher acame the first female Breetish prime meenister.[48]

Premiership o the Unitit Kinrick: 1979–1990

eeditThatcher acame Prime Meenister on 4 Mey 1979. Arrivin at Downing Street she said, paraphrasin the Prayer o Saunt Francis:

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony;

Where there is error, may we bring truth;

Where there is doubt, may we bring faith;

And where there is despair, may we bring hope.— Margaret Thatcher, in her remarks on becoming Prime Minister, [49]

Thatcher remained in office ootthrou the next decade. For muckle o her premiership, she wis descrived as the maist pouerfu wumman in the warld.[50][51][52][53][54]

Domestic affairs

eeditThatcher wis Leader o the Opposeetion an Prime Meenister at a time o increased racial tension in Breetain. Commentin on the local elections o Mey 1977, The Economist notit "The Tory tide swamped the smaller parties. That specifically includes the National Front, which suffered a clear decline from last year".[55][56] Her staundin in the polls rose bi 11% efter a Januar 1978 interview for World in Action in which she said "the British character has done so much for democracy, for law and done so much throughout the world that if there is any fear that it might be swamped people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in", as well as "in many ways [minorities] add to the richness and variety of this country. The moment the minority threatens to become a big one, people get frightened".[57][58] In the 1979 general election, the Conservatives attracted voters frae the Naitional Front, whose support awmaist collapsed.[59][60] In a meetin in Julie 1979 wi Foreign Secretar Lord Carrington an Hame Secretar Willie Whitelaw she objectit tae the nummer o Asie immigrants, in the context o leemitin the tot o Vietnamese boat fowk allaed tae settle in the UK tae less nor 10,000.[61]

As Prime Meenister, Thatcher met weekly wi Queen Elizabeth II tae discuss govrenment business, an thair relationship came unner close scrutiny.[62][63] Biografer John Campbell says thair relations war "punctiliously correct but there was little love lost on either side". The Queen's press secretar leaked anonymous rumours o a rift, which war offeecially denee'd bi the Palace. Campbell concludes that Thatcher haed "an almost mystical reverence for the institution of the monarchy" despite "trying to modernise the country and sweep away many of the values and practices which the monarchy perpetuated".[64] Thatcher later wrate: "I always found the Queen's attitude towards the work of the Government absolutely correct ... stories of clashes between 'two powerful women' were just too good not to make up."[65]

Economy an taxation

eeditThatcher's economic policy wis influenced bi monetarist thinkin an economists sic as Milton Friedman an Alan Walters.[66] Thegither wi Chancellor o the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe, she lawered direct taxes on income an increased indirect taxes.[67] She increased interest rates tae slaw the growthe o the money supplee an tharebi lawer inflation,[66] introduced cash leemits on public spendin, an reduced expenditur on social services sic as eddication an hoosin.[67] Her cuts in heicher eddication spendin resultit in her bein the first Oxford-eddicatit post-war Prime Meenister nae tae be awairdit an honorar doctorate bae the Varsity o Oxford, efter a 738 tae 319 vote o the govrenin assembly an a student peteetion.[68]

Some Heathite Conservatives in the Cabinet, the sae-cried "wets", expressed dout ower Thatcher's policies.[69] The 1981 Ingland riots resultit in the Breetish media discussin the need for a policy U-turn. At the 1980 Conservative Pairty conference, Thatcher addressed the issue directly, wi a speech written bi the playwricht Ronald Millar[70] that included the lines: "You turn if you want to. The lady's not for turning!"[69]

Thatcher's job appruival ratin fell tae 23% bi December 1980, lawer nor recordit for ony previous Prime Meenister.[71] As the recession o the early 1980s deepened she increased taxes,[72] despite concerns expressed in a statement signed bi 364 leadin economists issued taewart the end o Mairch 1981.[73] Bi 1982, the UK begoud tae experience signs o economic recovery;[74] inflation wis doun tae 8.6% frae a heich o 18%, but unemployment wis ower 3 million for the first time syne the 1930s.[75] Bi 1983 oweraw economic growthe wis stranger an inflation an mortgage rates war at thair lawest levels syne 1970, awtho manufacturin employment as a share o tot employment fell tae juist ower 30%,[76] wi tot unemployment remeenin heich, peakin at 3.3 million in 1984.[77]

Bi 1987, unemployment wis fawin, the economy wis stable an strang an inflation wis law. Opeenion polls shawed a comfortable Conservative lead, an local cooncil election results haed an aa been successfu, promptin Thatcher tae cry a general election for 11 Juin that year, despite the deidline for an election still bein 12 month awey. The election saw Thatcher re-electit for a third successive term.[78]

Industrial relations

eeditThatcher wis committit tae reducin the pouer o the tred unions, whase leadership she accused o unnerminin pairlamentar democracy an economic performance throu strick action.[79] Several unions lenched stricks in response tae legislation introduced tae crib thair pouer, but reseestance eventually collapsed.[80] Anerly 39% o union members votit for Labour in the 1983 general election.[81] The miners' strick o 1984–85 wis the biggest confrontation atween the unions an the Thatcher govrenment.

Privatisation

eeditThe policy o privatisation haes been cried "a crucial ingredient o Thatcherism".[82] Efter the 1983 election the sale o state utilities acceleratit;[83] maur than £29 billion wis raised frae the sale o naitionalised industries, an anither £18 billion frae the sale o cooncil hooses.[84] The process o privatisation, especially the preparation o naitionalised industries for privatisation, wis associatit wi merked impruivements in performance, pairteecularly in terms o labour productivity.[85]

Northren Ireland

eeditIn 1980 an 1981, Proveesional Erse Republican Airmy (IRA) an Erse Naitional Leeberation Airmy (INLA) preesoners in Northren Ireland's Maze Prison cairied oot hunger stricks in an effort tae regain the status o poleetical preesoners that haed been remuived in 1976 bi the precedin Labour govrenment.[86] Bobby Sands begoud the 1981 strick, sayin that he wad fest till daith unless preeson inmates wan concessions ower thair leevin condeetions.[86] Thatcher refuised tae coontenance a return tae poleetical status for the preesoners, declarin "Crime is crime is crime; it is not political",[86] but nivertheless the UK govrenment privately contactit republican leaders in a bid tae bring the hunger stricks tae an end.[87] Efter the daiths o Sands an nine ithers, the strick endit. Some richts war restored tae paramilitar preesoners, but nae offeecial recogneetion o poleetical status.[88] Violence in Northren Ireland escalatit signeeficantly during the hunger stricks; in 1982 Sinn Féin politeecian Danny Morrison descrived Thatcher as "the biggest bastard we have ever known".[89]

Thatcher narraely escaped injury in an IRA assassination attempt at a Brighton hotel early in the mornin on 12 October 1984.[90] Five fowk war killed, includin the wife o Cabinet Meenister John Wakeham. Thatcher wis stayin at the hotel tae attend the Conservative Pairty conference, which she inseestit shoud open as scheduled the follaein day.[90] She delivered her speech as planned,[91] awbeit rewritten frae her oreeginal draft,[92] in a muive that wis widely supportit athort the poleetical spectrum an enhanced her popularity wi the public.[93]

On 6 November 1981, Thatcher an Erse Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald haed established the Anglo-Erse Inter-Govrenmental Cooncil, a forum for meetins atween the twa govrenments.[88] On 15 November 1985, Thatcher an FitzGerald signed the Hillsborough Anglo-Irish Agreement, the first time a Breetish govrenment haed gien the Republic o Ireland an adveesory role in the govrenance o Northren Ireland. In protest the Ulster Says No muivement attractit 100,000 tae a rally in Belfast,[94] Ian Gow resigned as Meenister o State in the HM Thesaury,[95][96] an aw fifteen Unionist MPs resigned thair pairlamentar seats; anerly ane wis nae returned in the subsequent bi-elections on 23 Januar 1986.[97]

Environment

eeditThatcher supported an active climate pertection policy an wis instrumental in the creaution o the Environmental Protection Act 1990 an in foundin the Intergovrenmental Panel on Climate Chynge an the Breetish Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research in Exeter.[98] She helped tae put climate chynge, acid rain an general pollution in the Breetish mainstream in the early 1980s,[98] an gained distinction as the first warld leader tae wairn o global wairmin.[99] Her speeches includit ane tae the Ryal Society on 27 September 1988[100] an tae the UN General Assembly in November 1989. Houever, upon her retirement as Prime Meenister in 1990, she missed the Earth Summit 1992 an acame sceptical aboot climate chynge policy.[98][99]

Foreign affairs

eeditThatcher's first foreign policy creesis came wi the 1979 Soviet invasion o Afghanistan. She condemned the invasion, said it shawed the bankruptcy o a détente policy, an helped convince some Breetish athletes tae boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics. She gae waik support tae US Preses Jimmy Carter wha tried tae punish the USSR wi economic sanctions. Breetain's economic situation wis precarious, an maist o NATO wis reluctant tae cut tred ties.[101]

Thatcher acame closely aligned wi the Cauld War policies o US Preses Ronald Reagan, based on thair shared distrust o Communism.[80] A disgreement came in 1983 when Reagan did nae consult wi her on the invasion o Grenada.[102] During her first year as Prime Meenister she supportit NATO's deceesion tae deploy US nuclear cruise an Pershing II missiles in Wastren Europe[80] an permittit the US tae station mair nor 160 cruise missiles at RAF Greenham Common, stairtin on 14 November 1983 an triggerin mass protests bi the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[80] She bocht the Trident nuclear missile submarine seestem frae the US tae replace Polaris, triplin the UK's nuclear forces[103] at an eventual cost o mair nor £12 billion (at 1996–97 prices).[104]

On 2 Apryle 1982 the rulin militar junta in Argentinae ordered the invasion o the Breetish-controlled Falkland Islands an Sooth Georgie, triggerin the Falklands War.[105] At the suggestion o Harold Macmillan an Robert Armstrong,[106] she set up an chaired a smaw War Cabinet (formally cried ODSA, Owerseas an Defence committee, Sooth Atlantic) tae tak chairge o the conduct o the war,[107] which bi 5–6 Apryle haed authorised an dispatched a naval task force tae retak the islands.[108] Argentinae surrendered on 14 Juin an the operation wis hailed a success, naewistaundin the daiths o 255 Breetish servicemen an 3 Falkland Islanders. The "Falklands factor", an economic recovery beginnin early in 1982, an a bitterly dividit opposeetion aw contreibutit tae Thatcher's seicont election veectory in 1983.[109]

In September 1982 she veesitit Cheenae tae discuss wi Deng Xiaoping the sovereignty o Hong Kong efter 1997. Cheenae wis the first communist state Thatcher haed veesitit an she wis the first Breetish prime meenister tae veesit Cheenae. Efter the ta-year negotiations, Thatcher concedit tae the PRC govrenment an signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration in Beijing in 1984, greein tae haund ower Hong Kong's sovereignty in 1997.[110]

Awtho sayin that she wis in favour o "peaceful negotiations" tae end apartheid,[111] Thatcher stuid against the sanctions imponed on Sooth Africae bi the Commonweel an the EC.[112] Thatcher dismissed the African Naitional Congress (ANC) in October 1987 as "a typical terrorist organisation".[113][114]

The Thatcher govrenment supportit the Khmer Rouge keepin thair seat in the UN efter thay war oostit frae pouer in Cambodie bi the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. Awtho Thatcher denied it at the time, it wis revealed in 1991 that frae 1983 the SAS wis sent tae saicretly train the "non-Communist" members o the CGDK tae fecht against the Vietnamese-backed Fowkrepublic o Kampuchea govrenment.[115][116][117]

Thatcher an her pairty haed supportit Breetish membership o the EC in the 1975 naitional referendum,[118] but she believed that the role o the organisation shoud be leemitit tae ensurin free tred an effective competeetion, an feared that the EC's approach wis at odds wi her views on smawer govrenment an deregulation.[119]

Thatcher wis ane o the first Wastren leaders tae respond wairmly tae reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Follaein Reagan–Gorbachev summit meetins an reforms enactit bi Gorbachev in the USSR, she declared in November 1988 that "We're not in a Cold War now", but raither in a "new relationship much wider than the Cold War ever was".[120]

Challenges tae leadership an resignation

eeditThatcher wis challenged for the leadership o the Conservative Pairty bi the little-kent backbench MP Sir Anthony Meyer in the 1989 leadership election.[121] O the 374 Conservative MPs eligible tae vote, 314 votit for Thatcher an 33 for Meyer.[121] Her supporters in the pairty viewed the result as a success, an rejectit suggestions that thare wis discontent within the pairty.[121]

Opeenion polls in September 1990 reportit that Labour haed established a 14% lead ower the Conservatives,[122] an bi November the Conservatives haed been trailin Labour for 18 months.[123] Thir ratins, thegither wi Thatcher's combative personality an willinness tae owerride colleagues' opeenions, contreibuted tae discontent within her pairty.[124] On 1 November 1990, Geoffrey Howe, the last remeenin member o Thatcher's oreeginal 1979 cabinet, resigned frae his poseetion as Depute Prime Meenister ower her refuisal tae gree tae a timetable for Breetain tae jyn the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.[122][125] His resignation pruived fatal tae Thatcher's premiership.[126]

On 14 November, Michael Heseltine moontit a challenge for the leadership o the Conservative Pairty.[127] Opeenion polls haed indicatit that he wad gie the Conservatives a naitional lead ower Labour.[128] Awtho Thatcher wan the first ballot wi 204 tae 152 votes an 16 abstentions, Heseltine haed attractit sufficient support tae force a seicont ballot. Unner pairty rules, Thatcher nae anerly needit tae win a majority, but her margin ower Heseltine haed tae be equivalent tae 15% o the 372 Conservative MPs in order tae win the leadership election ootricht; wi 54.8% against 40.9% for Heseltine, she came up fower votes short.[129] Thatcher ineetially statit that she intendit to "fight on and fight to win" the seicont ballot, but consultation wi her Cabinet persuadit her tae widraw.[124][130] Efter an audience wi the Queen, cryin ither warld leaders, an makkin ane feenal Commons speech,[131] she left Downing Street in tears. She reportitly regairdit her oustin as a betrayal.[132]

Her resignation surprised internaitional observers includin Henry Kissinger an Mikhail Gorbachev.[133] Thatcher wis replaced as Prime Meenister an pairty leader bi her Chancellor John Major, wha prevailed ower Heseltine in the subsequent ballot. Major owersaw an upturn in Conservative support in the 17 months leadin up tae the 1992 general election an led the Conservatives tae thair fowert successive veectory on 9 Apryle 1992.[134] Thatcher haed favoured Major ower Heseltine in the leadership contest, but her support for him waikened in later years.[135]

Later life

eeditThatcher returned tae the backbenches as a constituency pairlamentarian efter leavin the premiership.[136] Her domestic appruival ratin recovered efter her resignation; the balance o public opeenion wis that her govrenment haed been guid for the kintra.[137][138] Aged 66, she retired frae the Hoose at the 1992 general election, sayin that leavin the Commons wad allae her mair freedom tae speak her mynd.[139]

Post-Commons: 1992–2003

eeditUpon leavin the Hoose o Commons, Thatcher acame the first umwhile Prime Meenister tae set up a foondation;[140] the Breetish weeng o the Margaret Thatcher Foundation wis dissolved in 2005 acause o financial difficulties.[141] She wrote twa volumes o memoirs, The Downing Street Years (1993) an The Path to Power (1995). In 1991 she an her husband Denis muived tae a hoose in Chester Square, a residential gairden square in central Lunnon's Belgravia destrict.[142] Thatcher wis hired bi the tobaccae company Philip Morris as a "geopoleetical consultant" in Julie 1992, for $250,000 per year an an annual contreibution o $250,000 tae her foondation.[143]

In August 1992 she cried for NATO tae stap the Serbie assault on Goražde an Sarajevo tae end ethnic cleansin during the Bosnie War. She made a series o speeches in the Lairds creeticisin the Maastricht Treaty,[139] describing it as "a treaty too far" an statit: "I could never have signed this treaty."[144] She citit A. V. Dicey when statin that as aw three main pairties war in favour o the treaty, the fowk shoud hae thair say in a referendum.[145] Rfter Tony Blair's election as Labour Pairty leader in 1994, Thatcher praised Blair as "probably the most formidable Labour leader since Hugh Gaitskell", addin: "I see a lot of socialism behind their front bench, but not in Mr Blair. I think he genuinely has moved."[146] Blair reciprocated in describing Thatcher as a "thoroughly determined person, and that is an admirable quality".[147]

At the 2001 general election, Thatcher supportit the Conservative campaign, as she haed done in 1992 an 1997, an in the Conservative leadership election follaein its defeat, she endorsed Iain Duncan Smith ower Kenneth Clarke.[148] In 2002 she encouraged George W. Bush tae aggressively tackle the "unfinished business" o Iraq unner Saddam Hussein,[149] an praised Tony Blair for his "strong, bold leadership" in staundin wi Bush in the Iraq War.[150]

She broached the same subject in her Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World, which wis published in Apryle 2002 an dedicatit tae Ronald Reagan, writin that thare wad be na peace in the Middle East till Saddam Hussein wis toppled. Her beuk an aa said that Israel must tred laund for peace, an that the European Union (EU) wis "fundamentally unreformable", "a classic utopian project, a monument to the vanity of intellectuals, a programme whose inevitable destiny is failure".[151] She argued that Breetain shoud renegotiate its terms o membership or ense leave the EU an jyn the North American Free Trade Area.[152]

Follaein several smaw strokes she wis advised bi her doctors nae tae engage in further public speakin.[153] On 23 Mairch 2002, she annoonced that on the advice o her doctors she wad cancel aw planned speakin engagements an accept na mair.[154]

On 26 Juin 2003, Thatcher's husband Sir Denis dee'd o pancreatic cancer, an wis crematit on 3 Julie.[155]

Feenal years: 2003–2013

eeditOn 11 Juin 2004, Thatcher, against doctor's orders, attendit the state funeral service for Ronald Reagan.[156] She delivered her eulogy via videotape; in view o her heal, the message haed been pre-recordit several months earlier.[157][158] Thatcher flew tae Californie wi the Reagan entourage, an attendit the memorial service an interment ceremony for the preses at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.[159] In early 2005 Thatcher creeticised the wey the deceesion tae invade Iraq haed been made twa years previously. Awtho she still supportit the intervention tae topple Saddam Hussein, she said that as a scientist, she wad ayeweys leuk for "facts, evidence and proof", afore committin the airmed forces.[160]

Thatcher celebratit her 80t birthday at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Hyde Park, Lunnon, on 13 October 2005; guests includit the Queen, the Duke o Edinburgh, Princess Alexandra an Tony Blair.[161] Geoffrey Howe, bi then Laird Howe o Aberavon, wis an aa present, an said o his umwhile leader: "Her real triumph was to have transformed not just one party but two, so that when Labour did eventually return, the great bulk of Thatcherism was accepted as irreversible."[162] Accordin tae a later airticle in The Daily Telegraph, Thatcher's dauchter Carol first revealed that her mither haed dementia in 2005, sayin that "Mum doesn't read much any more because of her memory loss ... It's pointless. She can't remember the beginning of a sentence by the time she reaches the end".[163] She later recoontit hou she wis first struck bi her mither's dementia when in conversation Thatcher confuised the Falklands an Yugoslav conflicts; she recried the pyne o needin tae tell her mither repeatitly that her husband Denis wis deid.[164]

In 2006, Thatcher attendit the offeecial Washington, D.C. memorial service tae commemorate the fift anniversary o the 11 September attacks on the US. She wis a guest o Vice Preses Dick Cheney, an met Secretar o State Condoleezza Rice during her veesit.[165] In Februar 2007 Thatcher acame the first leevin Breetish prime meenister tae be honoured wi a statue in the Hooses o Pairlament. The bronze statue staunds opposite that o her poleetical hero, Sir Winston Churchill's,[166] an wis unveiled on 21 Februar 2007 wi Thatcher in attendance; she made brief remerks in the Members' Lobby o the Commons: "I might have preferred iron – but bronze will do ... It won't rust."[166]

Daith an funeral: 2013

eeditBaroness Thatcher dee'd on 8 Apryle 2013, at the age o 87, efter sufferin a stroke. She haed been stayin at a suite in the Ritz Hotel in Lunnon syne December 2012 efter haein difficulty wi stairs at her Chester Square hame in Belgravia.[167] Reactions tae the news o Thatcher's daith]] war mixed in the UK, rangin frae tributes laudin her as Breetain's greatest-ever peacetime Prime Meenister tae public celebrations o her daith an expressions o personalised vitriol.[168]

Details o Thatcher's funeral haed been greed wi her in advance.[169] She received a ceremonial funeral, includin full militar honours, wi a kirk service at St Paul's Cathedral on 17 Apryle.[170][171] Queen Elizabeth II an the Duke o Edinburgh attendit her funeral,[172] the seicont time in the Queen's reign that she haed attendit the funeral o ony o her umwhile Prime Meenisters (the first bein that o Winston Churchill in 1965).[173]

Efter the service at St Paul's Cathedral, Thatcher's bouk wis crematit at Mortlake Crematorium, whaur her husband haed been crematit. On 28 September a service for Thatcher wis held in the Aw Saunts Chapel o the Royal Hospital Chelsea's Margaret Thatcher Infirmary. In a private ceremony Thatcher's ess war interred in the grunds o the hospital, next tae thae o her husband.[174][175]

Notes

eedit- ↑ In her forewird tae the Conservative manifesto o 1979, Thatcher wrate o "a feeling of helplessness, that we are a once great nation that has somehow fallen behind".[1]

See forby

eeditReferences

eedit- ↑ "1979 Conservative Party General Election Manifesto". conservativemanifesto.com. Retrieved 28 Julie 2009.

- ↑ Beckett (2006), p. 1.

- ↑ Beckett (2006), p. 5.

- ↑ Beckett (2006), p. 6.

- ↑ Blundell (2008), pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Beckett (2006), p. 12.

- ↑ Blundell (2008), p. 23.

- ↑ Blundell (2008), pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Beckett (2006), p. 16.

- ↑ a b c d Beckett (2006), p. 22.

- ↑ Moore, Charles (5 Februar 2009). "Golly: now we know what's truly offensive". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 Apryle 2017.

- ↑ J.C. (21 October 2012). "Gaffe-ology: why Mitchell had to go". The Economist. Retrieved 29 Apryle 2017.

In 1948 Aneurin Bevan called the Conservative Party "lower than vermin", a comment that lost Labour thousands of moderate votes at the following election. The Tories embraced the phrase; some formed the Vermin Club in response (Margaret Thatcher was a member).

- ↑ a b Blundell (2008), p. 36.

- ↑ Information, Reed Business (7 Julie 1983). "Cream of the crop at Royal Society". New Scientist. 99 (1365): 5. Retrieved 25 Januar 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ Belz, Mindy (4 Mey 2013). "Weather maker". World Magazine. Archived frae the original on 3 Februar 2019. Retrieved 7 Juin 2017.

- ↑ Filby, Eliza (14 Apryle 2013). "Margaret Thatcher: her unswerving faith shaped by her father". The Telegraph.

- ↑ a b c Beckett (2006), pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Blundell (2008), p. 37.

- ↑ "Sir Denis Thatcher, Bt". The Daily Telegraph. 27 Juin 2003. Retrieved 6 Januar 2012.

- ↑ Campbell (2000), p. 100.

- ↑ Beckett (2006), p. 27.

- ↑ "No. 41842". The London Gazette. 13 October 1959. p. 6433.

- ↑ a b c Runciman, David (6 Juin 2013). "Rat-a-tat-a-tat-a-tat-a-tat". London Review of Books. Retrieved 11 Juin 2013.

- ↑ "HC S 2R [Public Bodies (Admission of the Press to Meetings) Bill] (Maiden Speech)". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 5 Februar 1960.

- ↑ Sandbrook, Dominic (9 Apryle 2013). "Viewpoint: What if Margaret Thatcher had never been?". BBC. Retrieved 16 Juin 2013.

- ↑ Reitan (2003), p. 4.

- ↑ a b c Scott-Smith, Giles (Winter 2003). ""Her Rather Ambitious Washington Program": Margaret Thatcher's International Visitor Program Visit to the United States in 1967" (PDF). Contemporary British History. Routledge – Taylor and Francis. 17 (4): 65–86. doi:10.1080/13619460308565458. ISSN 1743-7997. Archived frae the original (PDF) on 26 November 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ Wapshott (2007), p. 64.

- ↑ "Sexual Offences (No. 2)". Hansard. 731: 267. 5 Julie 1966. Archived frae the original on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 7 Juin 2017.

- ↑ Thatcher (1995), p. 150.

- ↑ "Medical Termination of Pregnancy Bill". Hansard. 732: 1165. 22 Julie 1966. Archived frae the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 7 Juin 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher's timeline: From Grantham to the House of Lords, via Arthur Scargill and the Falklands War". Independent. 8 Apryle 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Wapshott (2007), p. 65.

- ↑ Reitan (2003), p. 14.

- ↑ a b c Wapshott (2007), p. 76.

- ↑ Hickman, Martin (9 August 2010). "Tories move swiftly to avoid 'milk-snatcher' tag". The Independent. Archived frae the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ a b c Reitan (2003), p. 15.

- ↑ Smith, Rebecca (8 August 2010). "How Margaret Thatcher became known as 'Milk Snatcher'". The Sunday Telegraph. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ Thatcher (1995), p. 182.

- ↑ a b Reitan (2003), p. 16.

- ↑ Naughton, Philippe (18 Julie 2005). "Thatcher leads tributes to Sir Edward Heath". The Times. Retrieved 14 October 2008.[deid airtin]

- ↑ Philip Cowley and Matthew Bailey, "Peasants' Uprising or Religious War? Re-Examining the 1975 Conservative Leadership Contest", British Journal of Political Science (2000) 30#4 pp. 599–629

- ↑ "Press Conference after winning Conservative leadership (Grand Committee Room)". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ↑ Moore, Thatcher 1:394–395, 430

- ↑ "How Thatcher tried to thwart devolution". The Scotsman. 27 Apryle 2008. Archived frae the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 20 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ Beckett (2010), chapter 7.

- ↑ "7 September 1978: Callaghan accused of running scared". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008. Retrieved 13 Januar 2012.

- ↑ David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh, The British general election of 1979 (1980).

- ↑ "Remarks on becoming Prime Minister (St Francis's prayer)". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 4 Mey 1979. Retrieved 21 Mairch 2017.

- ↑ Bern, Paula (Februar 1987). How to Work for a Woman Boss, Even If You'd Rather Not (1st ed.). Dodd Mead. p. 43. ISBN 978-0396088394.

- ↑ Ogden, Chris (1990). Maggie: An Intimate Portrait of a Woman in Power (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 9, 12. ISBN 978-0671667603.

- ↑ Current Biography Yearbook. 50 (1989 ed.). H. W. Wilson Co. 1990. p. 567.

- ↑ Sheehy, Gail (1989). "Gail Sheehy on the most powerful woman in the world". Vanity Fair. Vol. 52. p. 102.

- ↑ Eisner, Jane (7 Juin 1987). "The most powerful woman in the world". The Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine. p. 1. ASIN B006RKBPBK.

- ↑ "Votes go to Tories, and nobody else". The Economist. 263 (6976). 14 Mey 1977. pp. 24–28.

- ↑ Conservative Party Campaign Guide Supplement 1978. Published by the Conservative and Unionist Central Office.

- ↑ "Mrs Thatcher fears people might become hostile if immigrant flow is not cut". The Times. 31 Januar 1978.

- ↑ "Britain: Facing a Multiracial Future". Time. 27 August 1979. Archived frae the original on 24 Julie 2013. Retrieved 20 Januar 2011.

- ↑ Reitan (2003), p. 26.

- ↑ Ward, Paul (2004). Britishness since 1870. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-415-22016-3. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ↑ Swaine, Jon (30 December 2009). "Margaret Thatcher complained about Asian immigration to Britain". The Daily Telegraph. Archived frae the original on 20 Januar 2011. Retrieved 20 Januar 2011.

- ↑ Reitan (2003), p. 28.

- ↑ Seward (2001), p. 154.

- ↑ Campbell, Margaret Thatcher: The Iron Lady 2:464

- ↑ Thatcher (1993), p. 18.

- ↑ a b Childs (2006), p. 185.

- ↑ a b Reitan (2003), p. 30.

- ↑ "29 January 1985: Thatcher snubbed by Oxford dons". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2007.

- ↑ a b "10 October 1980: Thatcher 'not for turning'". On this day 1950–2005. BBC News. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ↑ Jones, Kavanagh & Moran (2007), p. 224.

- ↑ Thornton (2006), p. 18.

- ↑ Reitan (2003), p. 31.

- ↑ "An avalanche of economists". The Times. 31 Mairch 1981. p. 17. Retrieved 12 Januar 2011.

- ↑ Floud & Johnson (2004), p. 392.

- ↑ "26 January 1982: UK unemployment tops three million". On this day 1950–2005. BBC News. 2008. Retrieved 16 Apryle 2010.

- ↑ Rowthorn, Robert; Wells, John R. (12 November 1987). De-Industrialization and Foreign Trade. Cambridge University Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0521263603.

- ↑ O'Grady, Sean (16 Mairch 2009). "Unemployment among young workers hits 15 per cent". The Independent. Archived frae the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ↑ "BBC Politics 97". BBC. 11 Juin 1987. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Thatcher (1993), pp. 97–98, 339–340.

- ↑ a b c d "Margaret Thatcher". CNN. Archived frae the original on 3 Julie 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ↑ Revzin, Philip (23 November 1984). "British Labor Unions Begin to Toe the Line, Realizing That the Times Have Changed". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Seldon & Collings (2000), p. 27.

- ↑ Feigenbaum, Henig & Hamnett (1998), p. 71.

- ↑ Marr (2007), p. 428.

- ↑ Parker, David; Martin, Stephen (Mey 1995). "The impact of UK privatisation on labour and total factor productivity". Scottish Journal of Political Economy. 42 (2): 216–217. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9485.1995.tb01154.x.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ a b c "3 October 1981: IRA Maze hunger strikes at an end". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008.

- ↑ Clarke, Liam (5 Apryle 2009). "Was Gerry Adams complicit over hunger strikers?". The Sunday Times. Archived frae the original on 1 Mairch 2011. Retrieved 20 Apryle 2009.

- ↑ a b "The Hunger Strike of 1981 – A Chronology of Main Events". CAIN, University of Ulster. Archived frae the original on 31 Mey 2007. Retrieved 27 Januar 2011.

- ↑ English (2005), pp. 207–208.

- ↑ a b "12 October 1984: Tory Cabinet in Brighton bomb blast". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ↑ Thatcher (1993), pp. 379–383.

- ↑ Travis, Alan (3 October 2014). "Thatcher was to call Labour and miners 'enemy within' in abandoned speech". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 Mey 2017.

- ↑ Lanoue, David J.; Headrick, Barbara (Spring 1998). "Short-Term Political Events and British Government Popularity: Direct and Indirect Effects". Polity. 30 (3): 423, 427, 431, 432. doi:10.2307/3235208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ "Anglo Irish Agreement Chronology". CAIN, University of Ulster. Archived frae the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 27 Januar 2011. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ "15 November 1985: Anglo-Irish agreement signed". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008. Retrieved 4 Mey 2010.

- ↑ Moloney (2002), p. 336.

- ↑ Cochrane (2001), p. 143.

- ↑ a b c Bell, Alice (9 Apryle 2013). "Greenwashing Thatcher's history does an injustice both to her and to science and technology policy". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ a b Booker, Christopher (12 Juin 2010). "Was Margaret Thatcher the first climate sceptic?". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 Juin 2017.

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher Speech to the Royal Society". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 27 September 1988. Retrieved 27 Apryle 2016.

- ↑ Daniel James Lahey, "The Thatcher government's response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, 1979–1980," Cold War History (2013) 13#1 pp 21–42.

- ↑ Gary Williams, "'A Matter of Regret': Britain, the 1983 Grenada Crisis, and the Special Relationship." Twentieth Century British History 12#2 (2001): 208–230.

- ↑ "Trident is go". Time. 28 Julie 1980. Archived frae the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 16 Januar 2011.

- ↑ "Vanguard Class Ballistic Missile Submarine". Federation of American Scientists. 5 November 1999. Retrieved 16 Januar 2011.

- ↑ Smith (1989), p. 21.

- ↑ Jackling (2005), p. 230.

- ↑ Hastings & Jenkins (1983), pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Hastings & Jenkins (1983), p. 95.

- ↑ Sanders, David; Ward, Hugh; Marsh, David (Julie 1987). "Government Popularity and the Falklands War: A Reassessment". British Journal of Political Science. 17 (3): 281–313. doi:10.1017/s0007123400004762.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ Reitan (2003), p. 116.

- ↑ See Hansard HC Debs (25 February 1988) vol 128 col 437 Archived 2016-03-19 at the Wayback Machine and Written Answers HC Deb (11 July 1988) vol 137 cols 3-4W Archived 2017-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Campbell (2011), p. 322.

- ↑ See Mr Winnick, Hansard HC Deb (13 November 1987) vol 122 col 701 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Howe (1994), pp. 477–478.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 26 October 1990, columns 655–667.

- ↑ "Butcher of Cambodia set to expose Thatcher's role". The Observer. 9 Januar 2000. Retrieved 26 Mey 2011.

- ↑ Pilger, John (17 Apryle 2000). "How Thatcher gave Pol Pot a hand". New Statesman.

- ↑ "Conservatives favor remaining in market". Wilmington Morning Star. United Press International. 4 Juin 1975. p. 5. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Senden (2004), p. 9.

- ↑ "Gorbachev Policy Has Ended The Cold War, Thatcher Says". The New York Times. Associated Press. 18 November 1988. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ a b c "5 December 1989: Thatcher beats off leadership rival". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ a b "1 November 1990: Howe resigns over Europe policy". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Ridley, Matt (25 November 1990). "Et Tu, Heseltine?; Unpopularity Was a Grievous Fault, and Thatcher Hath Answered for It". The Washington Post. p. 2.

- ↑ a b Whitney, Craig R. (23 November 1990). "Change in Britain; Thatcher Says She'll Quit; 11½ Years as Prime Minister Ended by Party Challenge". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Millership, Peter (1 November 1990). "Thatcher's Deputy Quits in Row over Europe". Reuters News.

- ↑ Walters, Alan (5 December 1990). "Sir Geoffrey Howe's resignation was fatal blow in Mrs Thatcher's political assassination". The Times.

- ↑ Marr (2007), p. 473.

- ↑ Lipsey, David (21 November 1990). "Poll swing followed downturn by Tories; Conservative Party leadership". The Times.

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher profile". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ "22 November 1990: Thatcher quits as prime minister". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "HC S: [Confidence in Her Majesty's Government]". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 22 November 1990. Retrieved 21 Mairch 2017.

- ↑ Marr (2007), p. 474.

- ↑ Travis, Alan (30 December 2016). "Margaret Thatcher's resignation shocked politicians in US and USSR, files show". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ↑ Kettle, Martin (4 Apryle 2005). "Pollsters taxed". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 Januar 2011.

- ↑ "Major attacks 'warrior' Thatcher". BBC News. 3 October 1999. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Reitan (2003), p. 118.

- ↑ Crewe, Ivor (Januar 1991). "Margaret Thatcher: As the British Saw Her" (PDF). The Public Perspective: 15, 16. Retrieved 1 Mairch 2017.

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013)". Ipsos MORI. 8 Apryle 2013. Archived frae the original on 22 Julie 2017. Retrieved 25 Mey 2017.

At the time of her resignation in November 1990, 52% of the public said that they thought her government had been good for the country and 40% that it had been bad.

- ↑ a b "30 June 1992: Thatcher takes her place in Lords". On this day 1950–2005. BBC. 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "Thatcher Archive". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ Barkham, Patrick (11 Mey 2005). "End of an era for Thatcher foundation". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ Taylor, Matthew (9 Apryle 2013). "Margaret Thatcher's estate still a family secret". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ "Tobacco Company Hires Margaret Thatcher as Consultant". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 19 Julie 1992. Retrieved 25 Mey 2017.

- ↑ "House of Lords European Communities (Amendment) Bill Speech". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 7 Juin 1993. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2007.

- ↑ "House of Commons European Community debate". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 20 November 1991. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2007.

- ↑ Castle, Stephen (28 Mey 1995). "Thatcher praises 'formidable' Blair". The Independent.

- ↑ Woodward, Robert (15 Mairch 1997). "Thatcher seen closer to Blair than Major". The Nation. Retrieved 25 Mey 2017.

- ↑ "Letter supporting Iain Duncan Smith for the Conservative leadership published in the Daily Telegraph". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 21 August 2001. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2007.

- ↑ Thatcher, Margaret (11 Februar 2002). "Advice to a Superpower". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Harnden, Toby (11 December 2002). "Thatcher praises Blair for standing firm with US on Iraq". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Glover, Peter C.; Economides, Michael J. (16 September 2010). Energy and Climate Wars: How Naive Politicians, Green Ideologues, and Media Elites are Undermining the Truth about Energy and Climate. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 1-4411-5307-1.

- ↑ Wintour, Patrick (18 Mairch 2002). "Britain must quit EU, says Thatcher". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 Mey 2014.

- ↑ "Statement from the office of the Rt Hon Baroness Thatcher LG OM FRS" (Press release). Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 22 Mairch 2002. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ Campbell (2003), pp. 796–798.

- ↑ "Lady Thatcher bids Denis farewell". BBC News. Retrieved 20 Januar 2011.

- ↑ "Thatcher: 'Reagan's life was providential'". CNN. 11 Juin 2004. Archived frae the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "Thatcher's final visit to Reagan". BBC News. 10 Juin 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Russell, Alec; Sparrow, Andrew (7 Juin 2004). "Thatcher's taped eulogy at Reagan funeral". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 Julie 2016.

- ↑ "Private burial for Ronald Reagan". BBC News. 12 Juin 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Grice, Andrew (13 October 2005). "Thatcher reveals her doubts over basis for Iraq war". The Independent. Archived frae the original on 31 Julie 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ "Thatcher marks 80th with a speech". BBC News. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "Birthday tributes to Thatcher". BBC News. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Langley, William (30 August 2008). "Carol Thatcher, daughter of the revolution". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 Februar 2013.

- ↑ Satter, Raphael G. (25 August 2008). "Book Recounts Margaret Thatcher's Decline". CBS. Associated Press. Retrieved 20 November 2008.[deid airtin]

- ↑ "9/11 Remembrance Honors Victims from More Than 90 Countries". United States Department of State. 11 September 2006. Archived frae the original on 22 September 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ a b "Iron Lady is honoured in bronze". BBC News. 21 Februar 2007. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2007.

- ↑ Swinford, Steven (8 Apryle 2013). "Margaret Thatcher: final moments in hotel without her family by her bedside". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Burns, John F.; Cowell, Alan (10 Apryle 2013). "Parliament Debates Thatcher Legacy, as Vitriol Flows Online and in Streets". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ Wright, Oliver (8 Apryle 2013). "Funeral will be a 'ceremonial' service in line with Baroness Thatcher's wishes". The Independent. Retrieved 12 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ "Ex-Prime Minister Baroness Thatcher dies, aged 87". BBC News. 8 Apryle 2013. Retrieved 8 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher funeral set for next week". BBC News. 9 Apryle 2013. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher: Queen leads mourners at funeral". BBC News. 17 Apryle 2013. Retrieved 4 Mey 2013.

- ↑ Davies, Caroline (10 Apryle 2013). "Queen made personal decision to attend Lady Thatcher's funeral". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 Mey 2013.

- ↑ "Baroness Thatcher's ashes laid to rest". The Telegraph. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher's ashes laid to rest at Royal Hospital Chelsea". BBC News. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

Bibliografie

eedit- Beckett, Clare (2006). Margaret Thatcher. Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904950-71-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blundell, John (2008). Margaret Thatcher: A Portrait of the Iron Lady. Algora. ISBN 978-0-87586-630-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, John (2000). Margaret Thatcher; Volume One: The Grocer's Daughter. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-7418-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reitan, Earl Aaron (2003). The Thatcher Revolution: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, and the Transformation of Modern Britain, 1979–2001. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-2203-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wapshott, Nicholas (2007). Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher: A Political Marriage. Sentinel. ISBN 1-59523-047-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thatcher, Margaret (1995). The Path to Power. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-638753-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckett, Andy (2010). When the Lights Went Out; Britain in the Seventies. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22137-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seward, Ingrid (2001). The Queen and Di: The Untold Story. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-561-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thatcher, Margaret (1993). The Downing Street Years. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255354-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Childs, David (2006). Britain since 1945: a political history (6th ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-39326-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Bill; Kavanagh, Dennis; Moran, Michael (2007). "Media organisations and the political process". Politics UK (6 ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-2411-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thornton, Richard C. (2006). The Reagan Revolution II: Rebuilding the Western Alliance. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-1356-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Floud, Roderick; Johnson, Paul (2004). The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52738-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seldon, Anthony; Collings, Daniel (2000). Britain Under Thatcher. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-31714-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Feigenbaum, Harvey; Henig, Jeffrey; Hamnett, Chris (1998). Shrinking the State: The Political Underpinnings of Privatization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63918-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marr, Andrew (2007). A History of Modern Britain. Pan. ISBN 978-0-330-43983-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- English, Richard (2005). Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517753-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moloney, Ed (2002). A Secret History of the IRA. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32502-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cochrane, Feargal (2001). Unionist Politics and the Politics of Unionism Since the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Cork University Press. ISBN 1-85918-259-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Gordon (1989). Battles of the Falklands War. I. Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-1792-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackling, Roger (2005). "The Impact of the Falklands Conflict on Defence Policy". In Badsey, Stephen; Grove, Mark; Havers, Rob (eds.). The Falklands Conflict Twenty Years On: Lessons for the Future (Sandhurst Conference Series). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35030-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hastings, Max; Jenkins, Simon (1983). Battle for the Falklands. Norton. ISBN 0-393-30198-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howe, Geoffrey (1994). Conflict of Loyalty. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-59283-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Senden, Linda (2004). Soft Law in European Community Law. Hart Publishing. ISBN 1-84113-432-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)