Testicle

The "Scots" that wis uised in this airticle wis written bi a body that haesna a guid grip on the leid. Please mak this airticle mair better gin ye can. |

The testicle (frae Laitin testiculus, diminutive o testis, meanin "witness" o virility,[1] plural testes) is the male gonad in ainimals. Lik the ovaries tae which they are homologous, testes are components o baith the reproductive seestem an the endocrine seestem. The primary functions o the testes are tae produce sperm (spermatogenesis) an tae produce androgens, primarily testosterone.

| Testicle | |

|---|---|

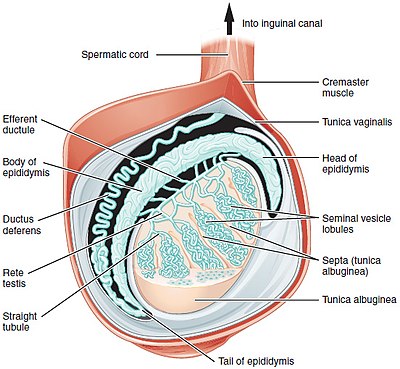

Inner wirkins o the testicles. | |

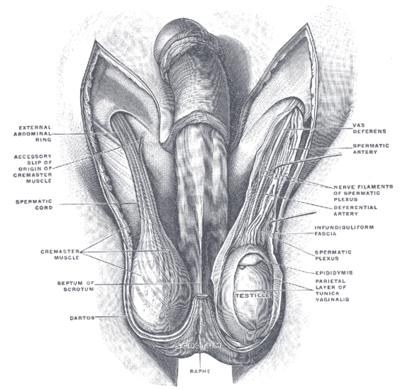

Diagram o male (human) testicles | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Testicular artery |

| Vein | Testicular vein, Pampiniform plexus |

| Nerve | Spermatic plexus |

| Lymph | Lumbar lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Laitin | testis |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | Testicle |

| TA | A09.3.01.001 |

| FMA | 7210 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structur

eeditAppearance

eeditMales hae twa testicles o seemilar size conteened within the scrotum, that is an extension o the abdominal wall. Scrotal asymmetry is nae unusual: ane testicle extends forder doun intae the scrotum nor the ither due tae differences in the anatomy o the vasculatur.

Meisurment

eeditThe vollum o the testicle can be estimatit bi palpating it an comparin it tae ellipsoids o kent sizes. Anither method is to use calipers (an orchidometer) or a ruler aither on the person or on an ultrasoond eemage tae obteen the three meisurments o the x, y, an z axes (lenth, deepth an weenth). Thir measurements can then be uised tae calculate the vollum, uisin the formula for the vollum o an ellipsoid: 4/3 π × (lenth/2) × (weenth/2) × (deepth/2).

The dimensions o the average adult testicle are up tae 2 inches lang, 0.8 inches in breidth, an 1.2 inches in hicht (5 × 2 × 3 cm). The Tanner scale for the maturity o male genitals assigns a maturity stage tae the calculatit vollum rangin frae stage I, a vollum o less nor 1.5 ml; tae stage V, a vollum greater nor 20 ml. Normal vollum is 15 tae 25 ml; the average is 18 cm³ per testis (range 12 cm³ to 30 cm³.[2]

Internal structur

eeditDuct seestem

eeditThe testes are kivert bi a teuch membranous shell cried the tunica albuginea. Within the testes are verra fine coiled tubes cried seminiferous tubules. The tubules are lined wi a layer o cells (germ cells) that develop frae puberty throu auld age intae sperm cells (kent as spermatozoa or male gametes forby). The developin sperm travel throu the seminiferous tubules tae the rete testis locatit in the mediastinum testis, tae the efferent ducts, an then tae the epididymis whaur newly creatit sperm cells matur (see spermatogenesis). The sperm muive intae the vas deferens, an are eventually expelled throu the urethra an oot o the urethral orifice throu muscular contractions.

Primary cell teeps

eedit- Within the seminiferous tubules

- Here, germ cells develop intae spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids an spermatozoon throu the process o spermatogenesis. The gametes conteen DNA for fertilisation o an ovum[3]

- Sertoli cells – the true epithelium o the seminiferous epithelium, creetical for the support o germ cell development intae spermatozoa. Sertoli cells secrete inhibin.[4]

- Peritubular myoid cells surroond the seminiferous tubules.[5]

- Atween tubules (intersteetial cells)

- Leydig cells – cells localized atween seminiferous tubules that produce an secrete testosterone an ither androgens important for sexual development an puberty, seicontar sexual chairacteristics lik facial hair, sexual behaviour an libido, supportin spermatogenesis an erectile function. Testosterone controls testicular vollum forby.

- Present as weel are:

- Immatur Leydig cells

- Intersteetial macrophages an epithelial cells.

Bluid supplee an lymphatic drainage

eeditBluid supplee an lymphatic drainage o the testes an scrotum are distinct:

- The paired testicular arteries arise directly frae the abdominal aorta an strynd throu the inguinal canal, while the scrotum an the rest o the freemit genitalia is supplee'd bi the internal pudendal artery (itsel a branch o the internal iliac artery).

- The testis haes collateral bluid supply frae 1. the cremasteric artery (a brainch o the inferior epigastric artery, that is a branch o the external iliac artery), an 2. the artery tae the ductus deferens (a brainch o the inferior vesical artery, that is a brainch o the internal iliac artery). Tharefore, if the testicular artery is ligatit, e.g., in a Fowler-Stevens orchiopexy for a heich undescendit testis, the testis will uisually survive on thir ither bluid supplies.

- Lymphatic drainage o the testes follaes the testicular arteries back tae the paraaortic lymph nodes, while lymph frae the scrotum drains tae the inguinal lymph nodes.

Layers

eeditMony anatomical featurs o the adult testis reflect its developmental oreegin in the abdomen. The layers o tishie enclosin ilk testicle are derived frae the layers o the anterior abdominal waw. Notably, the cremasteric muscle arises frae the internal oblique muscle.

The bluid–testis barrier

eeditMuckle molecules canna pass frae the bluid intae the lumen o a seminiferous tubule due tae the presence o ticht junctions atween adjacent Sertoli cells. The spermatogonia are in the basal compartment (deep tae the level o the ticht junctions) an the mair matur forms such as primar an seicontar spermatocytes an spermatids are in the adluminal compairtment.

The function o the bluid–testis baurier (reid heichlicht in diagram abuin) mey be tae prevent an auto-immune reaction. Matur sperm (an thair antigens) arise lang efter immune tolerance is established in infancy. Tharefore, syne sperm are antigenically different frae sel tishie, a male ainimal can react immunologically tae his awn sperm. In fact, he is capable o makkin antibouks against them.

Injection o sperm antigens causes inflammation o the testis (auto-immune orchitis) an reduced fertility. Sicweys, the bluid–testis baurier mey reduce the likeliheid that sperm proteins will induce an immune response, reducin fertility an sae progeny.

Temperatur regulation

eeditSpermatogenesis is enhanced at temperaturs slichtly less nor core bouk temperatur.[6] The spermatogenesis is less efficient at lawer an heicher temperaturs nor 33 °C.[6] Acause the testes are locatit ootside the bouk, the smuith tishie o the scrotum can muive them closer or forder awey frae the bouk.[6] The temperatur o the testes is mainteened at 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit), i.e. twa degrees ablo the bouk temperatur o 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit). Heicher temperaturs affect spermatogenesis.[7] Thare are a nummer o mechanisms tae mainteen the testes at the optimum temperatur.[6]

Gene an protein expression

eeditThe human genome includes approximately 20,000 protein codin genes: 80% o thir genes are expressed in adult testes.[8] The testes have the heichest fraction o tishie teep-speceefic genes compared tae ither organs an tishies:[9] aboot 1000 o them are heichly speceefic for the testes,[8] an aboot 2,200 shaw an elevatit pattern o expression here. A majority o thir genes encode for proteins that are expressed in the seminiferous tubules an hae functions relatit tae spermatogenesis.[9][10] Sperm cells express proteins that result in the development o flagella; thir same proteins are expressed in the female in cells linin the fallopian tube, an cause the development o cilia. In ither wirds, sperm cell flagella an Fallopian tube cilia are homologous structurs. The testis-specific proteins that shaw the heichest level o expression are protamines.

Development

eeditThare are twa phases in that the testes growe substantially; namely in embryonic an pubertal age.

Embryonic

eeditIn mammalian development, the gonads are at first capable o acomin aither ovaries or testes.[11] In humans, stairtin at aboot week 4 the gonadal rudiments are present within the intermediate mesoderm adjacent tae the developin neers. At aboot week 6, sex cords develop within the formin testes. Thir are made up o early Sertoli cells that surroond an nurtur the germ cells that migrate intae the gonads shortly afore sex determination begins. In males, the sex-speceefic gene SRY that is foond on the Y-chromosome ineetiates sex determination bi dounstream regulation o sex-determinin factors, (sic as GATA4, SOX9 an AMH), that leads tae development o the male phenoteep, includin directin development o the early bipotential gonad doun the male path o development.

Testes follae the "path o strynd" frae heich in the posterior fetal abdomen tae the inguinal ring an ayont tae the inguinal canal an intae the scrotum. In maist cases (97% full-term, 70% preterm), baith testes hae stryndit bi birth. In maist ither cases, anerly ane testis fails tae strynd (cryptorchidism) an that will probably express itsel within a year.

Pubertal

eeditThe testes growe in response tae the stairt o spermatogenesis. Size depends on lytic function, sperm production (amoont o spermatogenesis present in testis), interstitial fluid, and Sertoli cell fluid production.

Clinical signeeficance

eedit

Pertection an injure

eedit- The testicles are weel kent tae be verra sensitive tae impact an injure. The pyne involved traivels up frae ilk testicle intae the abdominal cavity, via the spermatic plexus, that is the primar nerve o ilk testicle. This will cause pyne in the hip an the back. The pain uisually goes away in a few minutes.

- Testicular torsion is a medical emergency.

- Testicular ruptur is a medical emergency caused bi blunt force impact, shairp edge, or piercin impact tae ane or baith testicles.

- Penetratin injuries tae the scrotum mey cause castration, or pheesical separation or destruction o the testes, possibly alang wi pairt or aw o the penis, that results in tot sterility if the testicles are nae reattached quickly.

- Some jockstraps are designed tae provide support tae the testicles.[12]

Diseases an condeetions

eedit| Testicular disease | |

|---|---|

| Clessification an freemit resoorces | |

| Specialty | FETCH_WIKIDATA |

| ICD-10 | E29, N43-N44 |

| ICD-9-CM | 257, 603-604 |

| MeSH | D013733 |

- Testicular cancer an ither neoplasms – Tae impuive the chances o catchin possible cases o testicular cancer or ither heal issues early, regular testicular sel-examination is recommendit.

- Varicocele, swalt vein(s) frae the testes, uisually affectin the left side,[13] the testis uisually bein normal

- Hydrocele testis, swallin aroond testes caused bi accumulation o clear liquid within a membranous sac, the testis uisually bein normal

- Spermatocele, a retention cyst o a tubule o the rete testis or the heid o the epididymis distendit wi barely watyery fluid that conteens spermatozoa

- Endocrine disorders can n aw affect the size an function o the testis.

- Certaint inheritit condeetions involvin mutations in key developmental genes impair testicular strynd an aw, resultin in abdominal or inguinal testes that remeen nonfunctional an mey acome cancerous. Ither genetic condeetions can result in the loss o the Wolffian ducts an allou for the persistence o Müllerian ducts. Baith excess an deficient levels o estrogens can disrupt spermatogenesis an cause infertility.[14]

- Bell-clapper deformity is a deformity in that the testicle is nae attached tae the scrotal waws, an can rotate freely on the spermatic cord within the tunica vaginalis. It is the maist common unnerlyin cause o testicular torsion.

- Orchitis inflammation o the testicles

- Epididymitis, a pynefu inflammation o the epididymis or epididymides frequently caused bi bacterial infection but whiles o unkent oreegin.

- Anorchia, the absence o ane or baith testicles.

- Cryptorchidism or "unstryndit testicles", when the testicle daes nae strynd intae the scrotum o the infant boy.

Testicular enlairgement is an unspeceefic sign o various testicular diseases, an can be defined as a testicular size o mair nor 5 cm (lang axis) x 3 cm (short axis).[15]

Blue baws is a slang term for a temporar fluid congestion in the testicles an prostate region caused bi prolanged sexual arousal.

Testicular prostheses are available tae mimic the appearance and feel o ane or baith testicles, whan absent as frae injury or as treatment in association to gender dysphoria. Thare hae been some instances o thair implantation in dugs an aw.[16]

Effects o exogenous hormones

eeditTae some extent, it is possible tae chynge testicular size. Short o direct injury or subjectin them tae adverse condeetions, e.g., heicher temperatur nor thay are normally accustomed tae, thay can be shrunk bi competin against their intrinsic hormonal function throu the uise o externally admeenistered steroidal hormones. Steroids taken for muscle enhancement (especially anabolic steroids) eften hae the undesired side effect o testicular shrinkage.

Seemilarly, stimulation o testicular functions via gonadotropic-lik hormones mey enlarge thair size. Testes mey shrink or atrophy in hormone replacement therapy or throu chemical castration.

In aw cases, the loss in testes vollum corresponds wi a loss o spermatogenesis.

Society an cultur

eeditTesticles o a male cauf or ither fermstockin are cuiked an eaten in a dish whiles cried Rocky Mountain oysters.[17]

As early as 330 BC, Aristotle prescrived the ligation (tyin aff) o the left testicle in men wishin tae hae boys.[18] In the Middle Ages, men that wantit a boy whiles haed thair left testicle remuived. This wis acause fowk believed that the richt testicle made "boy" sperm an the left made "girl" sperm.[19]

Etymology

eeditAne theory aboot the etymology o the wird testis is based on Roman law. The oreeginal Laitin wird testis, "witness", wis used in the firmly established legal principle "Testis unus, testis nullus" (ane witness [equals] na witness), meanin that testimony bi ony ane person in coort wis tae be disregairdit unless corroboratit bi the testimony o at least anither. This led tae the common practice o producin twa witnesses, bribed tae testify the same wey in cases o lawsuits wi ulterior motives. Syne siv "witnesses" ayeweys came in pairs, the meanin wis accordinly extendit, eften in the diminutive (testiculus, testiculi).

Anither theory says that testis is influenced bi a lend translation, frae Greek parastatēs "defender (in law), supporter" that is "twa glands side bi side".[20]

Ither ainimals

eeditFreemit appearance

eeditIn shairks, the testicle on the richt side is uisually mair muckle, an in mony bird an mammal species, the left mey be the larger. The primitive jawless fish hae anerly a single testis, locatit in the midline o the bouk, awtho even this forms frae the fusion o paired structurs in the embryo.[21]

In saisonal breeders, the wecht o the testes eften increases in the breedin saison.[22] The testicles o a dromedary camel are 7–10 cm (2.8–3.9 in) lang, 4.5 cm (1.8 in) deep an 5 cm (2.0 in) in weenth. The richt testicle is eften smawer nor the left.[23] The testicles o a male reid tod atteen thair greatest wecht in December–Februar.[24] Spermatogenesis in male gowden jackals occurs 10–12 days afore the females enter estrus an, in this time, males' testicles treeple in wecht.[25]

Location

eeditInternal

eeditThe basal condeetion for mammals is tae hae internal testes.[26] Thare are some marsupials wi freemit testes[27] an Boreoeutherian mammals wi internal testes, sic as the rhinoceros.[28] Cetaceans sic as whauls an dowphins hae internal testes an aw.[29] As freemit testes wad increase drag in the watter thay hae internal testes that are keepit cuil bi special circulatory seestems that cuil the arterial bluid gaein tae the testes bi placin the arteries near veins bringin cuiled venous bluid frae the skin.[30][31]

Freemit

eeditBoreoeutherian laund mammals, the muckle group o mammals that includes humans, hae freemitised testes.[32] Thair testes function best at temperaturs lawer nor thair core bouk temperatur. Thair testes are locatit ootside o the bouk, suspendit bi the spermatic cord within the scrotum.

Thare are several hypotheses why maist boreotherian mammals hae fremmit testes that operate best at a temperatue that is slichtly less nor the core bouk temperatur, e.g. that it is stuck wi enzymes evolved in a caulder temperatur due tae freemit testes evolvin for different raisons, that the lawer temperatur o the testes semply is mair efficient for sperm production.

1) Mair efficient. The clessic hypothesis is that cuiler temperatur o the testes allous for mair efficient fertile spermatogenesis. In ither wirds, thare are na possible enzymes operatin at normal core bouk temperatur that are as efficient as the anes evolved, at least nane appearin in our evolution so faur.

Houiver, the quaisten remeens why birds despite haein verra heich core bouk temperaturs hae internal testes an did nae evolve freemit testes.[33] It wis ance theorised that birds uised their air sacs tae cuil the testes internally, but later studies revealed that birds' testes are able tae function at core bouk temperatur.[33]

Some mammals that hae saisonal breedin cycles keep thair testes internal till the breedin saison at that pynt thair testes strynd an increase in size an acome freemit.[34]

2) Irreversible adaptation tae sperm competeetion. It haes been suggestit that the auncestor o the boreoeutherian mammals was a smaw mammal that required verra muckle testes (aiblins raither lik thae o a hamster) for sperm competeetion an sicweys haed tae place its testes ootside the byle.[35] This led tae enzymes involved in spermatogenesis, spermatogenic DNA polymerase beta an recombinase activities evolvin a unique temperatur optimum, slichtly less nor core bouk temperatur. Whan the boreoeutherian mammals then diversifee'd intae forms that war muckler an/or did nae require intense sperm competeetion thay still produced enzymes that operatit best at cuiler temperaturs an haed tae keep thair testes ootside the bouk. This poseetion is made less parsimonious bi the fact that the kangaroo, a non-boreoeutherian mammal, has freemit testicles. The auncestors o kangaroos micht, separately frae boreotherian mammals, hae been subject to hivy sperm competeetion an sicweys developit freemit testes, houiver, kangaroo freemit testes are suggestive o a possible adaptive function for freemit testes in muckle ainimals.

3) Protection frae abdominal cavity pressure changes. Ane argiement for the evolution o freemit testes is that it pertects the testes frae abdominal cavity pressur chynges caused bi jimpin an gallopin.[36]

4) Pertection against DNA damage. Mild, transient scrotal heat stress causes DNA damage, reduced fertility an abnormal embryonic development in mice.[37] DNA strand breaks war foond in spermatocytes recovered frae testicles subjectit tae 40 °C or 42 °C for 30 meenits.[37] Thir findings suggest that the freemit location o the testicles provides the adaptive benefit o pertectin spermatogenic cells frae heat-induced DNA damage that coud itherwise lead tae infertility an germline mutation.

Size

eeditThe relative size o testes is eften influenced bi matin seestems.[38] Testicular size as a proportion o bouk wecht varies widely. In the mammalian kinrick, there is a tendency for testicular size tae correspond wi multiple mates (e.g., harems, polygamy). Production o testicular ootput sperm an spermatic fluid is lairger in polygamous ainimals, possibly a spermatogenic competeetion for survival. The testes o the richt whaul are likely tae be the maist muckle o ony animal, ilk wechtin aroond 500 kg (1,100 lb).[39]

Amang the Hominidae, gorillas hae little female promiscuity an sperm competeetion an the testes are smaw compared to bouk wecht (0.03%). Chimpanzees hae heich promiscuity an muckle testes compared tae bouk weight (0.3%). Human testicular size faws atween thir extremes (0.08%).[40]

Internal structur

eeditUnner a teuch membranous shell cried the tunica albuginea, the testis o amniotes, as well as some teleost fish, conteens verra fine coiled tubes cried seminiferous tubules.

Amphibians an maist fish dae nae possess seminiferous tubules. Instead, the sperm are produced in spherical structures cried sperm ampullae. Thir are saisonal structurs, releasin thair contents in the breedin saison, an then bein reabsorbed bi the bouk. Afore the next breedin saison, new sperm ampullae begin tae form an ripen. The ampullae are itherwise essentially identical tae the seminiferous tubules in heicher vertebrates, includin the same range o cell teeps.[21]

Gailerie

eedit-

Testicle

-

Testicle

-

Testicle hangin on cremaster muscle. Thir are twa halthy testicles. Heat causes them tae descend, allouin cuilin.

-

A healthy scrotum conteenin normal size testes. The scrotum is in ticht condition. The eemage shaws the textur an aw.

-

Testicle o a cat: 1: Extremitas capitata, 2: Extremitas caudata, 3: Margo epididymalis, 4: Margo liber, 5: Mesorchium, 6: Epididymis, 7: testicular artery an vene, 8: Ductus deferens

-

Testis surface

-

Testis cross section

-

The richt testis, exposed bi layin appen the tunica vaginalis.

-

Microscopic view o Rabbit testis 100×

-

Testicle

References

eedit- ↑ "Blackwell Synergy". Blackwell Synergy. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ [1]" By E. Nieschlag, Hermann M. Behre, H. van. Ahlen, Andrology: Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction"

- ↑ Histology, A Text and Atlas by Michael H. Ross and Wojciech Pawlina, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 5th ed, 2006

- ↑ Skinner M, McLachlan R, Bremner W (1989). "Stimulation of Sertoli cell inhibin secretion by the testicular paracrine factor PModS". Mol Cell Endocrinol. 66 (2): 239–49. doi:10.1016/0303-7207(89)90036-1. PMID 2515083.

- ↑ Arch Histol Cytol. 1996 Mar;59(1):1–13

- ↑ a b c d Mieusset, R; Bujan, L; Mansat, A; Pontonnier, F (1992). "Hyperthermie scrotale et infécondité masculine" (PDF). Progrès en Urologie (in French) (2): 31–36. Archived frae the original (PDF) on 3 Mairch 2016.

- ↑ 1942-, Van De Graaff, Kent M. (Kent Marshall), (1989). Concepts of human anatomy and physiology. Fox, Stuart Ira. (2nd ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers. p. 936. ISBN 0697056759. OCLC 19493880.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors leet (link)

- ↑ a b Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (23 Januar 2015). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science (in Inglis). 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900.

- ↑ a b Djureinovic, D.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.; Danielsson, A.; Lindskog, C.; Uhlén, M.; Pontén, F. (1 Juin 2014). "The human testis-specific proteome defined by transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling". MHR: Basic science of reproductive medicine. 20 (6): 476–488. doi:10.1093/molehr/gau018. ISSN 1360-9947.

- ↑ "The human proteome in testis - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org.

- ↑ Online textbook: "Developmental Biology" 6th ed. By Scott F. Gilbert (2000) published by Sinauer Associates, Inc. of Sunderland (MA).

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Suspensory Jockstrap for Scrotal/Testicle Support by FlexaMed: Health & Personal Care". www.Amazon.com. Retrieved 25 Januar 2018.

- ↑ "Varicocele". Kidshealth.org. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Sierens, J. E.; Sneddon, S. F.; Collins, F.; Millar, M. R.; Saunders, P. T. (2005). "Estrogens in Testis Biology". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1061: 65–76. doi:10.1196/annals.1336.008. PMID 16467258.

- ↑ Page 559 in: John Pellerito, Joseph F Polak (2012). Introduction to Vascular Ultrasonography (6 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455737666.

- ↑ "Neuticles.com". www.Neuticles.com. Retrieved 25 Januar 2018.

- ↑ "Reviving a very delicate delicacy". 13 September 2004. Retrieved 25 Januar 2018 – via news.BBC.co.uk.

- ↑ Hoag, Hannah. I'll take a girl, please... Cherry-picking from the dish of life. Drexel University Publication. Archived August 31, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Understanding Genetics". Genetics.TheTech.org. Archived frae the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 25 Januar 2018.

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

- ↑ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 385–386. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ A.D. Johnson (2 December 2012). Development, Anatomy, and Physiology. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-14323-3.

- ↑ Mukasa-Mugerwa, E. The Camel (Camelus dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review. pp. 11–3.

- ↑ Heptner & Naumov 1998, p. 537

- ↑ Heptner & Naumov 1998, pp. 154–155

- ↑ [2] Archived 2018-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe; Marilyn Renfree (30 Januar 1987). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- ↑ Schaffer, N. E., et al. "Ultrasonography of the reproductive anatomy in the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) Archived 2017-09-23 at the Wayback Machine." Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine (1994): 337-348.

- ↑ Rommel, Sentiel A., D. Ann Pabst, and William A. McLellan. "Functional anatomy of the cetacean reproductive system, with comparisons to the domestic dog." Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea. Science Publishers (2016): 127–145.

- ↑ Rommel, Sentiel A., D. Ann Pabst, and William A. McLellan. "Reproductive Thermoregulation in Marine Mammals: How do male cetaceans and seals keep their testes cool without a scrotum? It turns out to be the same mechanism that keeps the fetus cool in a pregnant female Archived 2017-09-23 at the Wayback Machine." American scientist 86.5 (1998): 440-448.

- ↑ Pabst, D. Ann, Sentiel A. Rommel, and WILLIAM A. McLELLAN. "Evolution of thermoregulatory function in cetacean reproductive systems." The Emergence of Whales. Springer US, 1998. 379-397.

- ↑ D. S. Mills; Jeremy N. Marchant-Forde (2010). The Encyclopedia of Applied Animal Behaviour and Welfare. CABI. pp. 293–. ISBN 978-0-85199-724-7.

- ↑ a b BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION 56, 1570–1575 (1997)- Determination of Testis Temperature Rhythms and Effects of Constant Light on Testicular Function in the Domestic Fowl (Gallus domesticus) Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Ask a Biologist Q&A / Human sexual physiology – good design?". Askabiologist.org.uk. 4 September 2007. Archived frae the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ "'The Human Body as an Evolutionary Patchwork' by Alan Walker, Princeton.edu". RichardDawkins.net. 10 Apryle 2007. Archived frae the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ "Science : Bumpy lifestyle led to external testes".

- ↑ a b Paul C, Murray AA, Spears N, Saunders PT (2008). "A single, mild, transient scrotal heat stress causes DNA damage, subfertility and impairs formation of blastocysts in mice". Reproduction. 136 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1530/REP-08-0036. PMID 18390691.

- ↑ Pitcher, T.E.; Dunn, P.O.; Whittingham, L.A. (2005). "Sperm competition and the evolution of testes size in birds". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 18: 557–567. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00874.x.

- ↑ Crane, J.; Scott, R. (2002). "Eubalaena glacialis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 1 Mey 2009.

- ↑ Shackelford, T. K.; Goetz, A. T. (2007). "Adaptation to Sperm Competition in Humans". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16: 47. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00473.x.