Chromosome

A chromosome (frae auncient Greek: χρωμόσωμα, chromosoma, chroma means colour, soma means bouk) is a DNA molecule wi pairt or aw o the genetic material (genome) o an organism. Maist eukaryotic chromosomes include packagin proteins that, aidit bi chaperone proteins, bind to an condense the DNA molecule tae prevent it frae acomin an unmanageable tangle.[1][2]

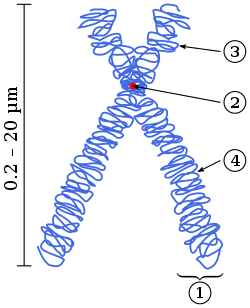

Chromosomes are normally veesible unner a licht microscope anly whan the cell is unnergaein the metaphase o cell diveesion. Afore this happens, ivery chromosome is copied ance (S phase), an the copy is jyned tae the oreeginal bi a centromere, resultin aither in an X-shapit structur (picturt tae the richt) if the centromere is locatit in the middle o the chromosome or a twa-airm structur if the centromere is locatit near ane o the ends. The oreeginal chromosome an the copy are nou cried sister chromatids. In metaphase the X-shape structur is cried a metaphase chromosome. In this heichly condensed form chromosomes are easiest tae distinguish an study.[3] In ainimal cells, chromosomes reach thair heichest compaction level in anaphase in segregation.[4]

Chromosomal recombination in meiosis an subsequent sexual reproduction play a seegneeficant role in genetic diversity. If thir structurs are manipulatit incorrectly, throu processes kent as chromosomal instability and translocation, the cell mey unnergae mitotic catastrophe an dee, or it mey unexpectitly evade apoptosis, leadin to the progression o cancer.

Some uise the term chromosome in a wider sense, tae refer tae the individualised portions o chromatin in cells, aither veesible or nae unner licht microscopy. Houiver, ithers uise the concept in a narraer sense, tae refer tae the individualised portions o chromatin in cell diveesion, veesible unner licht microscopy due tae heich condensation.

Etymology

eeditThe wird chromosome comes frae the Greek χρῶμα (chroma, "colour") an σῶμα (soma, "bouk"), descrivin thair strang stainin bi pairteecular dyes.[5] The term wis crautit bi von Waldeyer-Hartz,[6] referrin tae the term chromatin, that wis introduced bi Walther Flemming.

History o diskivery

eeditThe German scientists Schleiden,[3] Virchow an Bütschli war amang the first scientists that recognised the structurs nou fameeliar as chromosomes.[7]

Wilhelm Roux suggestit that ilk chromosome cairies a different genetic laid. Boveri wis able tae test an confirm this hypothesis. Aidit bi the rediskivery at the stairt o the 1900s o Gregor Mendel's earlier wark, Boveri wis able tae pynt oot the connection atween the rules o inheritance an the behaviour o the chromosomes. Boveri influenced twa generations o American cytologists: Edmund Beecher Wilson, Nettie Stevens, Walter Sutton an Theophilus Painter war aw influenced bi Boveri (Wilson, Stevens, an Painter actually wirkit wi him).[8]

In his famous textbeuk The Cell in Development and Heredity, Wilson airtit thegither the independent wark o Boveri an Sutton (baith aroond 1902) bi namin the chromosome theory o inheritance the Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory (the names are whiles reversed).[9] Ernst Mayr remerks that the theory wis hetly contestit bi some famous geneticists: William Bateson, Wilhelm Johannsen, Richard Goldschmidt an T.H. Morgan, aw o a raither dogmatic turn o mynd. Eventually, complete pruif cam frae chromosome maps in Morgan's awn lab.[10]

The nummer o human chromosomes wis published in 1923 by Theophilus Painter. Bi inspection throu the microscope, he coontit 24 pairs, that wad mean 48 chromosomes. His error wis copied bi ithers an it wis nae till 1956 that the true nummer, 46, wis determined bi Indonesie-born cytogeneticist Joe Hin Tjio.[11]

Prokaryotes

eeditThe prokaryotes – bacteria an archaea – teepically hae a single circular chromosome, but mony variations exeest.[12] The chromosomes o maist bacteria, that some authors prefer tae cry genophores, can range in size frae anerly 130,000 base pairs in the endosymbiotic bacteria Candidatus Hodgkinia cicadicola[13] an Candidatus Tremblaya princeps,[14] tae mair nor 14,000,000 base pairs in the sile-dwallin bacterium Sorangium cellulosum.[15] Spirochaetes o the genus Borrelia are a notable exception tae this arrangement, wi bacteria sic as Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause o Lyme disease, conteenin a single linear chromosome.[16]

Structur in sequences

eeditProkaryotic chromosomes hae less sequence-based structur nor eukaryotes. Bacteria teepically hae a ane-pynt (the oreegin o replication) frae that replication starts, whauras some archaea conteen multiple replication oreegins.[17] The genes in prokaryotes are eften organised in operons, an dae nae uisually conteen introns, unlik eukaryotes.

DNA packagin

eeditProkaryotes dae nae possess nuclei. Insteid, thair DNA is organised intae a structur cried the nucleoid.[18][19] The nucleoid is a distinct structur an occupies a defined region o the bacterial cell. This structur is, houiver, dynamic an is mainteened an remodeled bi the actions o a range o histone-lik proteins, that associate wi the bacterial chromosome.[20] In archaea, the DNA in chromosomes is even mair organised, wi the DNA packaged within structurs seemilar tae eukaryotic nucleosomes.[21][22]

Certaint bacteria an aw conteen plasmids or ither extrachromosomal DNA. Thir are circular structurs in the cytoplasm that conteen cellular DNA an play a role in horizontal gene transfer.[3] In prokaryotes an viruses,[23] the DNA is eften densely packed an organised; in the case o archaea, bi homology tae eukaryotic histones, an in the case o bacteria, bi histone-lik proteins.

Bacterial chromosomes tend tae be tethered tae the plasma membrane o the bacteria. In molecular biology application, this allous for its isolation frae plasmid DNA bi centrifugation o lysed bacteria an pelletin o the membranes (an the attached DNA).

Prokaryotic chromosomes an plasmids are, lik eukaryotic DNA, generally supercoiled. The DNA maun first be released intae its relaxed state for access for transcription, regulation, an replication.

Eukaryotes

eeditChromosomes in eukaryotes are componed o chromatin feebre. Chromatin feebre is made o nucleosomes (histone octamers wi pairt o a DNA straund attached tae an wrappit aroond it). Chromatin feebres are packaged bi proteins intae a condensed structur cried chromatin. Chromatin conteens the vast majority o DNA and a smaw amoont inheritit maternally, can be foond in the mitochondria. Chromatin is present in maist cells, wi a few exceptions, for ensaumple, reid bluid cells.

Chromatin allous the verra lang DNA molecules tae fit intae the cell nucleus. In cell diveesion chromatin condenses forder tae form microscopically veesible chromosomes. The structur o chromosomes varies throu the cell cycle. In cellular division chromosomes are replicatit, dividit, an passed successfully tae thair dauchter cells sae as tae ensur the genetic diversity an survival o their progeny. Chromosomes mey exeest as aither duplicatit or unduplicatit. Unduplicatit chromosomes are single dooble helixes, whauras duplicatit chromosomes conteen twa identical copies (called chromatids or sister chromatids) jynt bi a centromere.

Eukaryotes (cells wi nuclei sic as thae foond in plants, fungi, an ainimals) possess multiple lairge linear chromosomes conteened in the cell's nucleus. Ilk chromosome haes ane centromere, wi ane or twa airms projectin frae the centromere, awtho, unner mist circumstances, thir airms are nae veesible as sic. In addeetion, maist eukaryotes hae a smaw circular mitochondrial genome, an some eukaryotes mey hae additional smaw circular or linear cytoplasmic chromosomes.

In the nuclear chromosomes o eukaryotes, the uncondensed DNA exists in a semi-ordered structur, whaur it is wrapped aroond histones (structural proteins), formin a composite material cried chromatin.

Human chromosomes

eeditChromosomes in humans can be dividit intae twa teeps: autosomes (bouk chromosome(s)) an allosome (sex chromosome(s)). Certaint genetic traits are airtit tae a person's sex an are passed on throu the sex chromosomes. The autosomes conteen the rest o the genetic hereditary information. Aw act in the same wey in cell diveesion. Human cells hae 23 pairs o chromosomes (22 pairs o autosomes an ane pair o sex chromosomes), giein a tot o 46 per cell. In addeetion tae thir, human cells hae mony hunders o copies o the mitochondrial genome. Sequencin o the human genome haes providit a great deal o information aboot ilk o the chromosomes. Ablo is a table compilin stateestics for the chromosomes, based on the Sanger Institute's human genome information in the Vertebrate Genome Annotation (VEGA) database.[24] Nummer o genes is an estimate, as it is in pairt based on gene predeections. Tot chromosome lenth is an estimate as weel, based on the estimatit size o unsequenced heterochromatin regions.

| Chromosome | Genes[25] | Tot base pairs | % o bases | Sequenced base pairs[26] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2000 | 247,199,719 | 8.0 | 224,999,719 |

| 2 | 1300 | 242,751,149 | 7.9 | 237,712,649 |

| 3 | 1000 | 199,446,827 | 6.5 | 194,704,827 |

| 4 | 1000 | 191,263,063 | 6.2 | 187,297,063 |

| 5 | 900 | 180,837,866 | 5.9 | 177,702,766 |

| 6 | 1000 | 170,896,993 | 5.5 | 167,273,993 |

| 7 | 900 | 158,821,424 | 5.2 | 154,952,424 |

| 8 | 700 | 146,274,826 | 4.7 | 142,612,826 |

| 9 | 800 | 140,442,298 | 4.6 | 120,312,298 |

| 10 | 700 | 135,374,737 | 4.4 | 131,624,737 |

| 11 | 1300 | 134,452,384 | 4.4 | 131,130,853 |

| 12 | 1100 | 132,289,534 | 4.3 | 130,303,534 |

| 13 | 300 | 114,127,980 | 3.7 | 95,559,980 |

| 14 | 800 | 106,360,585 | 3.5 | 88,290,585 |

| 15 | 600 | 100,338,915 | 3.3 | 81,341,915 |

| 16 | 800 | 88,822,254 | 2.9 | 78,884,754 |

| 17 | 1200 | 78,654,742 | 2.6 | 77,800,220 |

| 18 | 200 | 76,117,153 | 2.5 | 74,656,155 |

| 19 | 1500 | 63,806,651 | 2.1 | 55,785,651 |

| 20 | 500 | 62,435,965 | 2.0 | 59,505,254 |

| 21 | 200 | 46,944,323 | 1.5 | 34,171,998 |

| 22 | 500 | 49,528,953 | 1.6 | 34,893,953 |

| X (sex chromosome) | 800 | 154,913,754 | 5.0 | 151,058,754 |

| Y (sex chromosome) | 50 | 57,741,652 | 1.9 | 25,121,652 |

| Total | 21,000 | 3,079,843,747 | 100.0 | 2,857,698,560 |

Karyotype

eeditIn general, the karyotype is the chairactereestic chromosome complement o a eukaryote species.[27] The preparation an study o karyotypes is pairt o cytogenetics.

Aberrations

eeditChromosomal aberrations are disruptions in the normal chromosomal content o a cell an are a major cause o genetic conditions in humans, sic as Down syndrome, awtho maist aberrations hae little tae na effect. Some chromosome abnormalities dae nae cause disease in cairiers, sic as translocations, or chromosomal inversions, awtho thay mey lead tae a heicher chance o beirin a bairn wi a chromosome disorder. Abnormal numbers o chromosomes or chromosome sets, cried aneuploidy, mey be lethal or mey gie rise tae genetic disorders.[28] Genetic coonselin is offered for faimilies that mey cairy a chromosome rearrangement.

The gain or loss o DNA frae chromosomes can lead tae a variety o genetic disorders. Human ensaumples include:

- Down syndrome, the maist common trisomy, usually caused bi an extra copy o chromosome 21 (trisomy 21). Chairactereestics include decreased muscle tone, stockier big, asymmetrical skull, slantin een an mild tae moderate developmental disability.[29]

- Edwards syndrome, or trisomy-18, the seicont maist common trisomy.[30] Symptoms include motor retardation, developmental disability an numerous congenital anomalies causin serious heal problems. Ninety percent o thae affectit die in infancy. Thay hae chairactereestic clenched haunds an owerlaippin fingers.

- Klinefelter syndrome (XXY). Men wi Klinefelter syndrome are uisually sterile an tend tae be tawer an hae langer airms an legs nor thair peers. Boys wi the syndrome are eften shy an quiet an hae a heicher incidence o speech delay an dyslexia. Withoot testosterone treatment, some mey develop gynecomastia in puberty.

References

eedit- ↑ Hammond, Colin M.; Strømme, Caroline B.; Huang, Hongda; Patel, Dinshaw J.; Groth, Anja (2017). "Histone chaperone networks shaping chromatin function". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 18 (3): 141–158. doi:10.1038/nrm.2016.159. ISSN 1471-0072.

- ↑ Wilson, John (2002). Molecular biology of the cell : a problems approach. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3577-6.

- ↑ a b c Schleyden, M. J. (1847). Microscopical researches into the accordance in the structure and growth of animals and plants.

- ↑ Wolfram, Antonin; Neumann, Heinz (2016). "Chromosome condensation and decondensation during mitosis". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. Elsevier Ltd. 40: 19. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2016.01.013. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ↑ Coxx, H. J. (1925). Biological Stains – A Handbook on the Nature and Uses of the Dyes Employed in the Biological Laboratory. Commission on Standardization of Biological Stains.

- ↑ Waldeyer-Hartz (1888). "Über Karyokinese und ihre Beziehungen zu den Befruchtungsvorgängen". Archiv für mikroskopische Anatomie und Entwicklungsmechanik. 32: 27.

- ↑ Fokin SI (2013). "Otto Bütschli (1848–1920) Where we will genuflect?" (PDF). Protistology. 8 (1): 22–35. Archived frae the original (PDF) on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Carlson, Elof A. (2004). Mendel's Legacy: The Origin of Classical Genetics (PDF). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-87969-675-7.

- ↑ Wilson, E.B. (1925). The Cell in Development and Heredity, Ed. 3. Macmillan, New York. p. 923.

- ↑ Mayr, E. (1982). The growth of biological thought. Harvard. p. 749.

- ↑ Matthews, Robert. "The bizarre case of the chromosome that never was" (PDF). Archived frae the original (PDF) on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 13 Julie 2013. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived frae the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ↑ Thanbichler M, Shapiro L (November 2006). "Chromosome organization and segregation in bacteria". Journal of Structural Biology. 156 (2): 292–303. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.007. PMID 16860572.

- ↑ Van Leuven JT, Meister RC, Simon C, McCutcheon JP (September 2014). "Sympatric speciation in a bacterial endosymbiont results in two genomes with the functionality of one". Cell. 158 (6): 1270–1280. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.047. PMID 25175626.

- ↑ McCutcheon JP, von Dohlen CD (August 2011). "An interdependent metabolic patchwork in the nested symbiosis of mealybugs". Current Biology. 21 (16): 1366–72. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.051. PMID 21835622.

- ↑ Han K, Li ZF, Peng R, Zhu LP, Zhou T, Wang LG, Li SG, Zhang XB, Hu W, Wu ZH, Qin N, Li YZ (2013). "Extraordinary expansion of a Sorangium cellulosum genome from an alkaline milieu". Scientific Reports. 3: 2101. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E2101H. doi:10.1038/srep02101. PMID 23812535.

- ↑ Hinnebusch J, Tilly K (December 1993). "Linear plasmids and chromosomes in bacteria". Molecular Microbiology. 10 (5): 917–22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00963.x. PMID 7934868.

- ↑ Kelman LM, Kelman Z (September 2004). "Multiple origins of replication in archaea". Trends in Microbiology. 12 (9): 399–401. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.001. PMID 15337158.

- ↑ Thanbichler M, Wang SC, Shapiro L (October 2005). "The bacterial nucleoid: a highly organized and dynamic structure". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 96 (3): 506–21. doi:10.1002/jcb.20519. PMID 15988757.

- ↑ Le TB, Imakaev MV, Mirny LA, Laub MT (November 2013). "High-resolution mapping of the spatial organization of a bacterial chromosome". Science. 342 (6159): 731–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..731L. doi:10.1126/science.1242059. PMID 24158908.

- ↑ Sandman K, Pereira SL, Reeve JN (December 1998). "Diversity of prokaryotic chromosomal proteins and the origin of the nucleosome". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 54 (12): 1350–64. doi:10.1007/s000180050259. PMID 9893710.

- ↑ Sandman K, Reeve JN (Mairch 2000). "Structure and functional relationships of archaeal and eukaryal histones and nucleosomes". Archives of Microbiology. 173 (3): 165–9. doi:10.1007/s002039900122. PMID 10763747.

- ↑ Pereira SL, Grayling RA, Lurz R, Reeve JN (November 1997). "Archaeal nucleosomes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (23): 12633–7. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9412633P. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.23.12633. PMID 9356501.

- ↑ Johnson JE, Chiu W (Apryle 2000). "Structures of virus and virus-like particles". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 10 (2): 229–35. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00073-7. PMID 10753814.

- ↑ Vega.sanger.ad.uk, all data in this table was derived from this database, November 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Ensembl genome browser 71: Homo sapiens – Chromosome summary – Chromosome 1: 1–1,000,000". apr2013.archive.ensembl.org. Retrieved 11 Apryle 2016.

- ↑ Sequenced percentages are based on fraction o euchromatin portion, as the Human Genome Project goals cried for determination o anerly the euchromatic portion o the genome. Telomeres, centromeres, an ither heterochromatic regions hae been left undetermined, as hae a smaw nummer o unclonable gaps. See https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/seq/ for mair information on the Human Genome Project.

- ↑ White, M. J. D. (1973). The chromosomes (6th ed.). London: Chapman and Hall, distributed by Halsted Press, New York. p. 28. ISBN 0-412-11930-7.

- ↑ Santaguida S, Amon A (August 2015). "Short- and long-term effects of chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 16 (8): 473–85. doi:10.1038/nrm4025. PMID 26204159.

- ↑ Miller KR (2000). "Chapter 9-3". Biology (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 194–5. ISBN 0-13-436265-9.

- ↑ "What is Trisomy 18?". Trisomy 18 Foundation. Archived frae the original on 30 Januar 2017. Retrieved 4 Februar 2017.